We have all probably seen the images of the damage that Hurricane Helene wreaked on Asheville and other parts of western North Carolina in September of 2024. After a wet fall that had many rivers at near-flood levels, the remnants of the hurricane blasted the area with tornadoes, high winds, and more drenching rain. The resulting floods were exacerbated by landslides, as whole mountainsides slipped into the valleys where most of the population resides. The damage is still being addressed eight months later—and will be for a long time to come.

But whether it is a 1,000-year event like the Asheville flood, a one-year slow leak from a refrigerator ice maker line, or a one-hour saturation from a broken water supply pipe, they all have real consequences for the quality of a building’s indoor air. That’s right—in short order, wet buildings can become indoor air quality nightmares.

Flooding Can Be Widespread or Confined to a Single Building

Before we get too deep into the details, it is critical to understand that there is the “official” definition of flooding and the more generic characterization of the term. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), flooding is when water overflows normally dry land from heavy rain, waves, snowmelt, or if dams or levees break. The more expansive meaning of the term, used by the restoration industry, describes flooding as any circumstance that allows normally dry surfaces to become partially or completely saturated.

From the restoration perspective, flooding can be individual, local, or widespread. As the subcategory implies, individual flooding affects a single building. The water source can be from overflowed tubs, plugged toilets, malfunctioning water valves, split plumbing lines, roof problems, foundation leaks, or even condensation from excess humidity. Such flooding can be sudden or build up over time.

Local flooding involves more than one building, although such events usually affect fewer than 100 structures. Sewer line blockages and backflow, rapid snowmelt, paving areas without providing adequate storm drains, and a host of other factors can lead to local flooding. In contrast to individual or local flooding, widespread flooding is typically the aftermath of natural or man-made disasters. As with the Hurricane Helene example cited previously, whole towns or regions can be impacted by a single widespread flooding event.

Regardless of the Scope of The Flood, Water-Damaged Buildings Quickly Develop IAQ Problems

The simple idea that buildings are designed to protect occupants from the elements should be the primary clue that water-damaged buildings (WDB) can pose danger to occupants. Flooding not substantially addressed within 24 hours poses a great risk to good indoor air quality (IAQ), as the wet building materials become a breeding ground for microorganisms—and not the type that are people-friendly!

If saturated porous items are not removed expeditiously after a flood, and the semi-porous and non-porous materials are not dried quickly, the bad organisms too small to see without a microscope will start to grow. The type of problem microbe and speed of its spread will be greatly influenced by the type of floodwater and wet material. Flooding from a sewage line or groundwater has many more “starter” organisms than a drinking water source that leaks. That explains why odors (the chemicals released by growing bacteria and mold) and colonies of slime and mold typically appear sooner when the floodwater is dirty.

Despite the fact that mold has received most of the attention over the past quarter century, the reality is that flooding that is not remediated properly produces a multitude of hazardous pathogens that send chemicals and particles into the air. Those airborne problems usually include some mix of1:

Actinobacteria – Tiny bacteria that release harmful chemicals and can trigger serious immune reactions.

Endotoxins – Toxic substances released by gram-negative bacteria.

Fungal colonies – Groups of fungi that deteriorate surfaces and release spores that impact occupant health.

Mycotoxins – Poisons released from numerous mold types that grow in water-damaged buildings.

Fungal fragments and mold metabolites – Dead mold parts that can cause inflammation.

Beta-glucans – Tiny mold particles that stay airborne and trigger strong immune reactions—even after mold is gone.

Other microbial toxins – Toxins that work together to overwhelm your body’s defenses.

Real Dangers From Unseen Hazards

The most frustrating aspect of any IAQ problem is that it cannot be seen. The old adage of “out of sight, out of mind” rings true with IAQ issues because people may not even know they have a problem with their air quality—they just sense that they do not feel well. Since each flood is different, no two WDB have exactly the same mix of air contaminants. This leads to a huge range of resident symptoms and significant difficulties for the medical professionals responding to occupant reports of ill health.

The pathogens in the microorganism “stew” that soon gets into the air in water-damaged buildings do not just irritate the lungs of the people who breathe it in—they can also affect the brain, immune system, hormones, and energy production. Worse yet, new studies prove that IAQ contaminants from WDB can team up with other toxins to supercharge inflammation and damage cells at a deep level2 .

Why The Type Of Flooding Matters

If all types of flooding can—and do—cause IAQ problems, why is the distinction in the scope important to take into consideration? The significance of the scope of flooding is that it directly impacts the ability of the occupants to promptly and properly address the water damage that is affecting the indoor air quality. Treating WDB indoor air quality issues with deodorizers, air purifiers, or a spray of some chemical “guaranteed” to eliminate the problem is sure to make the problem worse. Such secondary treatments are only effective after the water-damaged porous materials have been properly removed and the other wet areas thoroughly dried. Even then, spraying or fogging a chemical instead of doing the hard work of proper cleaning will not necessarily prevent microbial growth. Regardless of any treatment, any delay in the removal and drying process beyond 24 hours from the initial flooding will see the start of the microorganism growth cycle.

Due to the scale of the problem and the extent of damage in each impacted building, widespread flooding puts extra stress on restoration and repair resources. Everything from contractor availability, building supplies, and necessary equipment (extractors, drying units, air scrubbers, etc.) is in short supply after widespread flooding. Such disasters also trigger the arrival of volunteer groups to assist with the devastation. Depending on the group, their efforts at initial muck-out and tear-out may leave behind wet substrates and other conditions that foster the growth of the microbes.

Additionally, local and widespread flooding usually involves dirty water. Even well-intentioned volunteers may not know proper sanitization techniques. Despite the proliferation of it at disaster sites, and even its distribution by government agencies, spraying bleach as a decontamination approach is not the answer! Indeed, adding bleach or other chemicals to a water-damaged environment can actually make the IAQ worse by adding noxious products to the microbes compromising the air. The truism that “bad remediation is worse than no remediation at all” includes the IAQ component of such situations.

Preventing IAQ Problems from Flooding

In contrast, household flooding from clean water sources can sometimes be a do-it-yourself (DIY) effort. If physically capable, the occupants can respond to a flood and protect their indoor air quality by:

Stopping the source of the water causing the flooding as quickly as possible. This could require that the main water line for the entire building be temporarily shut off if the water is the result of a burst pipe or damaged control valve.

Removing waterlogged porous products. This includes carpets, rugs, furniture, clothes, and even drywall. Items that might be saved, like rugs, can be stored in a garage for later evaluation and processing by professionals.

Mopping or vacuuming up any excess standing water.

Drying of remaining semi-porous and non-porous materials (concrete slabs, block walls, wooden framing, etc.) with fans and drying equipment such as industrial-grade dehumidifiers. Such equipment is available from many rental businesses.

When to Call a Professional

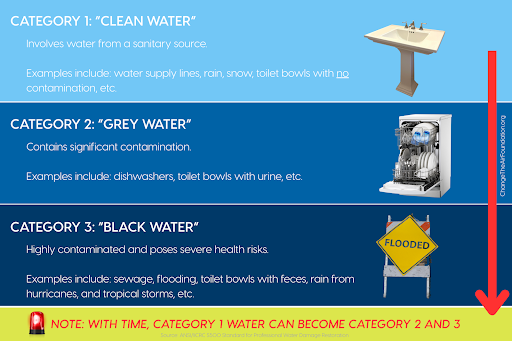

While minor flooding incidents in a single building may be appropriate for a DIY approach, there are a number of factors that quickly push such a situation to something that professionals should handle. The guidelines for the water damage restoration industry3 divide interior flood circumstances into three main types based on the source and level of contamination. These categories provide a great general rule for which projects can be DIY and which should require the assistance of a professional. Of the three classifications, as described below, only those that fit Category 1 are best suited for occupant remediation—knowing that compromised indoor air quality is a considerably higher risk with poor remediation of the other classes of water damage:

Category 1 (Clean Water): Involves water from a sanitary source.

Category 2 (Grey Water): Contains significant contamination.

Category 3 (Black Water): Highly contaminated and poses severe health risks.

Indeed, a large percentage of water damage restoration companies match those services with mold remediation for a reason: water damage is the precursor to mold growth. They get called in to fix buildings months after a resident thought they had handled their flooding problem. In addition, generally, any Category 2 or 3 flooding is covered under standard home or rental insurance policies. When in doubt, call in a professional. The health of the occupants is worth it.

A Final Thought

Any flood situation is a shock for the building occupant. Letting the shock paralyze the impacted parties into inaction is a sure way to allow the flood to turn into an indoor air quality nightmare.

Footnotes

1. Summarized from NWA Mold Inspector. (n.d.). Educational pamphlet on water-damaged buildings. Springdale, AR.

2. For example, see Shoemaker, R. C., & House, D. E. (2006). Sick building syndrome (SBS) and exposure to water-damaged buildings: Time series study, clinical trial and mechanisms. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 28(5), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2006.07.003

3. From Institute of Inspection Cleaning and Restoration Certification. (2021). ANSI/IICRC S500 Standard for Professional Water Damage Restoration (5th ed.).

About the Author

Michael A. Pinto is the owner of Pinto Solutions LLC, a consulting firm focused on identifying and managing indoor contaminants. He authored the first textbook on mold remediation and helped to develop many of the standards and guidelines used in the mold remediation industry. Michael can be reached at [email protected]

Related Resources from Change the Air Foundation:

Got Mold & Water Damage? Start Here! https://changetheairfoundation.org/mold-water-damage/

What To Do After a Hurricane https://changetheairfoundation.org/what-to-do-after-a-hurricane/

Hiring the Right Team & Order Of Events https://changetheairfoundation.org/mold-remediation-part-1/

Maximize Your Home Insurance Payout With A Public Adjuster https://changetheairfoundation.org/maximize-your-home-insurance-payout-with-a-public-adjuster/

Free Download: Five Signs of Water Damage https://changetheairfoundation.org/sdm_downloads/5-signs-of-water-damage/

Free Download: Moisture Basics https://changetheairfoundation.org/sdm_downloads/moisture-basics/

Free Download: Checklist: Where to Look For Mold & Water Damage https://changetheairfoundation.org/sdm_downloads/checklist-where-to-look-for-mold-water-damage/

Free Download: Mold Remediation At A Glance https://changetheairfoundation.org/remediation-guide/

Free Download: Questions to Ask When Hiring an IEP https://changetheairfoundation.org/sdm_downloads/questions-to-ask-when-hiring-an-indoor-environmental-professional-iep/

Free Download: Questions to Ask When Hiring a Remediation Company https://changetheairfoundation.org/sdm_downloads/questions-to-ask-when-hiring-a-remediation-company/